Parametric Estimating in the Age of AI: A Technical Perspective

Parametric estimating has always been slightly misunderstood. It is frequently described as a way to estimate earlier or estimate faster, but those descriptions miss the more important point. Parametric estimating is fundamentally about imposing structure on uncertainty at stages where the available information cannot support detailed estimating in any meaningful sense.

Many of the frustrations associated with parametric approaches stem from expecting them to behave like late-stage estimates when the conditions under which they are applied make that impossible. Parametric estimates improve decision quality relative to the alternatives available at early points in in the project lifecycle even when they are not able to predict final outturn cost to within five percent.

The Structural Problem Parametric Estimating Addresses

Early-stage estimating exists in a constrained environment. Scope is incomplete, design is immature, construction methods are provisional, and delivery context is often only partially defined. Yet critical decisions still need to be made: which options to advance, how much capital to reserve, where risk is concentrated, and whether a project is even viable.

Bottom-up estimating struggles here for structural reasons. When estimating a wastewater treatment plant at concept stage, you might know target flow rate and regulatory requirements, but you don't know pipe routes, excavation volumes, foundation details, or equipment specifications. You can make assumptions, but minor changes in those assumptions (switching from gravity to pumped collection, for example) can shift costs by twenty percent or more.

The resulting estimates look detailed because they contain many line items, but they're highly unstable. The estimator's judgement fills the gaps, but that judgement is difficult to scale, audit, or apply consistently across a portfolio of similar decisions.

Parametric estimating addresses this by explicitly trading detail for consistency. Cost is modelled as a function of drivers that can be defined early (flow rate, population equivalent, site constraints) and compared systematically. For that wastewater plant, you might model cost per population equivalent served, adjusted for site access and regulatory stringency. It's less detailed than a bottom-up estimate, but far more stable when design is still fluid.

This trade-off is rational, but it introduces challenges that are often underestimated.

The Data Reality: Why Your Historical Cost Database Is Lying to You

In theory, parametric estimating relies on stable relationships between cost and measurable drivers. In practice, historical data rarely reflects such stability cleanly.

Consider a typical database of fifty school construction projects spanning ten years. Surface-level, that looks like a solid foundation. But examine it closely and you commonly find:

- Twelve projects were design-build, the rest traditional procurement. Risk transfer patterns are fundamentally different

- Seven were phased refurbishments where separating new-build from adaptation costs is impossible

- Cost recording changed in year five when the organization switched accounting systems

- Three projects included abnormal site conditions that dominated final cost

- Inflation indices were applied inconsistently across cost categories

After filtering for comparability, you're left with perhaps fifteen truly similar projects. This pattern repeats across most infrastructure portfolios. What appeared to be abundant data is actually sparse, and sparsity creates fragility.

Normalization is not a preprocessing step. It's a core estimating judgement.

Decisions about which projects are comparable, how to adjust for context, which cost elements to include, and which outliers to exclude have first-order impacts on model behavior. When normalization is rushed or treated as a technical exercise divorced from estimating expertise, parametric models inherit bias and noise that later appear to be insight.

The challenge compounds when key drivers are missing entirely or recorded inconsistently. Many databases suffer from "site constraints" meaning something different to every project manager, delivery dates recorded as contract awards rather than practical completion, and variations sometimes included in final cost and sometimes recorded separately.

This is the environment parametric estimating actually operates in, not the clean datasets of textbook examples.

Classical Techniques: Knowing Their Boundaries

Traditional parametric methods (regression-based cost estimating relationships, scaling laws, power curve adjustments) remain highly effective within well-defined boundaries. Their enduring value lies in transparency and alignment with engineering intuition.

An experienced estimator can usually explain why a relationship exists and where it applies. They know that pump station costs scale with the 0.6 power of capacity because of economies of scale in equipment and structures. They understand why that relationship breaks down at very small scales where fixed costs dominate, or at very large scales where multiple units become necessary.

However, these techniques place increasing cognitive demands as complexity grows. Once you're juggling interactions between capacity, site constraints, regulatory environment, local labor markets, and delivery model, reasoning explicitly about all combinations becomes impractical. Simplifying assumptions get introduced (often sensible ones) but they're rarely revisited systematically as new data accumulates.

Small datasets exacerbate these problems. Regression models fitted to twenty projects can show statistical significance driven by three influential observations. Remove those three, and the relationship disappears. Overfitting is a genuine risk, particularly when models are recalibrated repeatedly without rigorous out-of-sample testing.

Classical parametric estimating works extremely well when:

- Asset types are delivered frequently with consistent scope definitions

- Cost drivers are well-understood and reliably recorded

- Delivery context is relatively stable

- Sample sizes exceed thirty comparable projects

Outside those conditions, additional analytical support becomes necessary.

Modern Analytical Approaches: Where They Actually Help

Machine learning won't magically fix bad data, but it does make certain problems more tractable. The gains are less about point accuracy and more about robust handling of uncertainty in sparse, noisy environments.

Regularization: Preventing Overconfidence

Regularization techniques (ridge regression, LASSO, elastic net) explicitly penalize model complexity. In estimating terms, they discourage fitting relationships that aren't strongly supported by data.

Practically, this means: if you have fifteen projects and six potential cost drivers, regularization will suppress weak or spurious relationships rather than chasing every fluctuation in the sample. The resulting model is more conservative and stable, which is precisely what you want at early stages.

In tunnel estimating applications, switching from standard regression to regularized models has been shown to reduce variance in cross-validation by thirty to forty percent without meaningfully changing median predictions. The model becomes less confident about marginal relationships and more robust to influential observations, exactly the behavior needed with limited data.

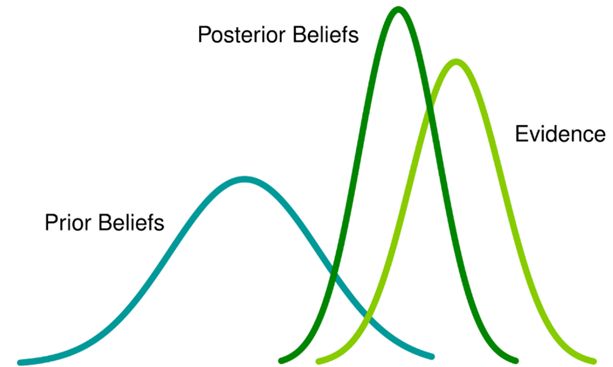

Bayesian Methods: Incorporating Engineering Knowledge

Bayesian approaches treat historical data as evidence that updates prior beliefs rather than as absolute truth. This mirrors how experienced estimators actually think.

If you're estimating a bridge type your organization has never built but have strong priors from similar structures, a Bayesian model lets you incorporate that knowledge explicitly. As local data accumulates, the model shifts weight appropriately. The mathematics formalizes what good estimators do intuitively, but with greater transparency.

When organizations enter new asset classes (such as offshore wind substations after years of onshore experience), hierarchical Bayesian models can transfer knowledge while allowing local calibration. Initial estimates become more stable than treating the new context as completely novel, and the framework provides explicit uncertainty bounds that reflect limited local evidence.

Handling High-Dimensional Spaces

Machine learning techniques can evaluate larger sets of candidate drivers than is practical manually. Rather than pre-selecting four or five variables based on intuition, models can consider twenty or thirty and identify which consistently contribute explanatory power.

This doesn't replace judgement. You still need estimators to define plausible drivers and logical constraints. But it provides evidence to challenge assumptions about what actually matters. Variables estimators considered critical can have minimal explanatory power once other factors are controlled for, and vice versa.

Important caveat: Higher dimensionality increases overfitting risk with small samples. This is where regularization becomes essential, not optional.

Explainability: Making Models Transparent

Modern explainability techniques (SHAP values, partial dependence plots, sensitivity analysis) let estimators understand model behavior rather than treating it as a black box.

You can see how changing site access from "urban constrained" to "greenfield" affects cost across the full range of project scales. You can identify which drivers dominate in different model regions. You can quantify how uncertainty in input parameters propagates to cost uncertainty.

This shifts the conversation from defending a single number to understanding cost behavior under different assumptions.

Model Governance: Where Implementation Actually Fails

Technical capability is necessary but insufficient. Most parametric modelling failures are governance failures, not analytical ones.

Key governance questions that organizations consistently under specify:

Who decides when a model is no longer applicable? Asset classes evolve. Delivery models shift. Regulatory environments change. You need explicit criteria for model retirement and clear authority to make that call, ideally before the model produces obviously wrong results on a critical decision.

How do you handle estimator resistance? The estimator who's used their spreadsheet successfully for fifteen years has legitimate expertise. Forcing adoption of new methods without respecting that knowledge creates opposition. The solution is hybrid models where experienced estimators define boundaries and constraints, and analytical techniques operate within them.

What's the process for model updates? Models should be living tools, updated as projects complete and new data becomes available. But updates need discipline. You can't recalibrate every time a result is inconvenient. Define update triggers: minimum new project count, significant market shifts, major methodological changes.

How do you prevent model shopping? When multiple models exist, there's temptation to run all of them and select the most favorable result. Establish protocols: define which model applies under which conditions, require documentation when deviating from standard practice, make approval hierarchies explicit.

Without governance frameworks addressing these questions, even excellent models produce organizational dysfunction.

Validation: Beyond Simple Backtesting

Model validation with sparse data requires more sophistication than simple holdout samples.

For datasets under thirty projects, leave-one-out cross-validation provides more robust assessment than single holdout. Every project serves as a test case, predicted using a model trained on all remaining data. This maximizes learning from limited samples while still testing predictive performance.

For time-series data, use expanding window validation: train on years one through three, test on year four; train on years one through four, test on year five. This respects temporal ordering and tests whether models degrade as conditions change.

The outturn paradox: Final project costs include risks that crystallized and variations that occurred. Your parametric model can't predict which risks will manifest, only their distribution. When validating against actuals, you're testing whether uncertainty bounds are calibrated, not whether point predictions match.

A model that's "wrong" fifty percent of the time but captures true cost within stated confidence intervals eighty percent of the time is far more useful than one that appears accurate on average but systematically under-represents uncertainty.

Validation should assess:

- Calibration of uncertainty bounds, not just point accuracy

- Stability across different project types and delivery contexts

- Sensitivity to influential observations

- Degradation over time as delivery environment evolves

Implementation Realities: What You Actually Need

Theory is one thing. Monday morning is another.

Computational infrastructure: You don't need cloud platforms or specialized software to start. Python or R environments running on standard laptops suffice for most parametric modelling. Structured databases matter more than computational power. Excel files with inconsistent schemas are the real bottleneck.

Skillset evolution: Estimators don't need to become data scientists, but basic statistical literacy becomes essential. Understanding what regularization does, why sample size matters, and how to interpret confidence intervals shouldn't be specialized knowledge.

Quick wins: Start with a narrow scope. Pick one asset type with reasonable data coverage where current estimating methods are frustrating. Build a simple regularized model with strong estimator input on drivers and constraints. Use it alongside existing methods initially, not as replacement. Learn what works before scaling.

Change management: Treat model introduction as methodology change, not technical implementation. Involve estimators early. Make models transparent. Accept that hybrid approaches (analytical models with expert adjustment) are often more effective than pure automation.

A Decision Framework: What to Use When

Use classical parametric techniques when:

- You have thirty-plus comparable projects with consistent recording

- Relationships between cost and drivers are well-understood

- Stakeholders value transparency and engineering intuition over sophisticated analytics

- Analytical infrastructure is limited

Consider ML-augmented approaches when:

- Data is sparse (under twenty comparable projects) or noisy

- Multiple delivery models or contexts need accommodation

- You're managing portfolios where consistency matters more than individual accuracy

- You have analytical capability and estimator buy-in

Avoid parametric methods entirely when:

- Projects are genuinely unique with no meaningful comparables

- Scope definition is so uncertain that even high-level drivers are speculative

- Political or commercial factors dominate cost more than technical characteristics

- You're at a project stage where detailed estimating is feasible and appropriate

Where This Is Heading

The trajectory is clear: parametric estimating is moving from artisanal practice (highly skilled individuals applying judgement to limited data) toward more structured, auditable, systematically improvable processes.

AI doesn't eliminate the need for estimating expertise. It provides tools that let estimators work at higher levels of abstraction, focusing on what matters: defining relevant drivers, understanding context, translating uncertainty into decision support, rather than fighting data quality issues or manually tracking hundreds of marginal correlations.

The organizations that succeed will be those that recognize parametric estimating was never about producing precise numbers early. It was always about making uncertainty visible, structured, and comparable so that better decisions could be made with imperfect information.

That objective hasn't changed. We simply have better tools to pursue it honestly.